By Aleen Anderias

It was Palm Sunday at my local Armenian Church, and we had gathered to celebrate the resurrection of Christ. At the ripe age of 11, I was hoping to find peace and connection with my faith, but I couldn’t help but see girls my age staring at me with disapproval. I couldn’t help but wonder if they were scrutinizing my short skirt with its pattern of colorful melons or my black top that revealed my shoulders.

After the service, I ran into an old friend at the church, who introduced me to the same girls who had pouty and dissatisfied expressions. I was willing to see past their first impressions of me, but before I knew it, they had gathered in the girl’s bathroom, and their whispering came to a halt when I stepped in. Later, I found out that their whispers made fun of my physical appearance and behavior, claiming that I wasn’t Armenian or Iraqi but simply some “fake white girl” who speaks Armenian poorly.

Art can be a catalyst for inspiring artists to explore different fields of creativity on their own terms.

The embarrassment and hurt I felt caused me to suppress my feelings. I did exactly what they said of me, adopting my so-called “white girl” persona, and settling on the idea of being a third-culture kid.

Years later, during my junior and senior years in high school, I was in the International Baccalaureate curriculum. I gravitated towards the high-level Visual Arts course within this program. As an artist myself, I found this to be the perfect opportunity for my voice be heard; I created a series of paintings to reflect what being Armenian meant to me and the struggles I went through to find my identity.

Throughout my entire series, I was heavily inspired by Marc Chagall, Natalia Goncharova and Salvador Dali. These artists represent different spectrums of abstract art. Through these styles, I developed my style of figurative folk compositions where in each piece, there were faces of specific individuals that impacted my journey of being a third-culture kid. In every piece, I included a character that would represent me.

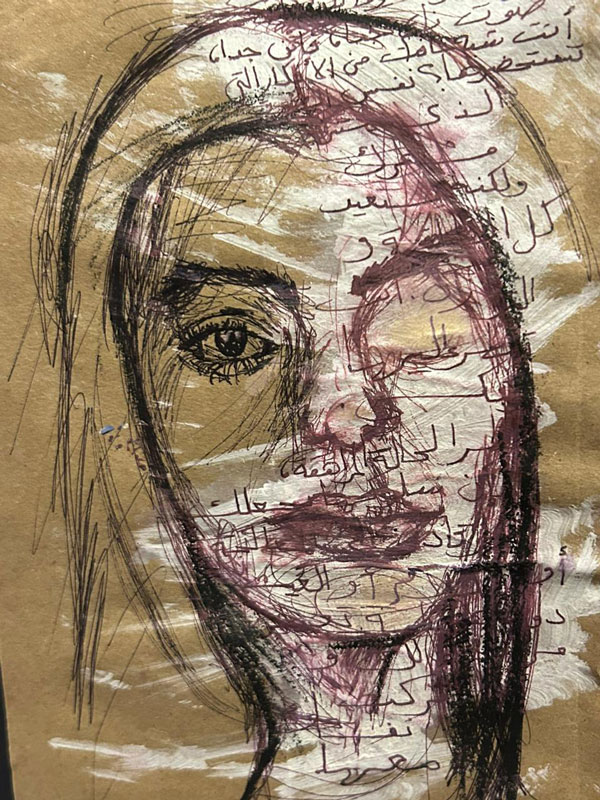

American University of Sharjah student and artist Salma Ghalwash, who paints self-portraits, finds that she dislikes the word “identity” because it’s ambiguous. She frequently changes her views on her own identity, which is reflected in her artwork by intentionally altering her appearance because she doesn’t focus on realism or accuracy, but instead on a feeling she can’t articulate verbally.

Ghalwash said that one of her paintings has a poem in Arabic that she had written even though she usually doesn’t use the language for creative expression. Having never lived in Egypt, Ghalwash felt both an attachment and disconnect to the language. Ghalwash added that in her early childhood experiences, people hadn’t been the kindest towards her because she doesn’t speak Arabic fluently even though she understands it well.

“It comes from a place of longing; however, I can put whatever flaw I may have or my being, as a product of society and combined cultures, into a limitless art form and it fulfills me,” said Ghalwash.

In my conversation with Ghalwash, I learned that we had a similar upbringing that revolved around the expat culture of the United Arab Emirates, the mutual feeling of “being from nowhere but somewhere,” being comfortable in English compared to our mother tongues, and how art is a tool for finding a sense of belonging.

For a third-culture kid, art can be impactful and a powerful source of self-expression because it gives an artist that space to resolve complex emotions and identity issues they cannot communicate. It is a process of healing and catharsis; it can also bring people together through empathy.

Art is the bridge to connect various cultural identities and embrace unique perspectives. It can also be a catalyst for inspiring artists to explore different fields of creativity on their own terms.

Though the path to self-acceptance and self-discovery may never end, art is a continual reminder of our transformation through visual communication, which has no limit.