By Abdullah Al-Tekreeti

On average, a person in New York spends five dollars on a cup of coffee. Of this five-dollar bill, a few dollars go to the coffee shop as profit, while some cover running costs, trickling down the supply chain. Somewhere along this chain, a child in Brazil, skin baked by the unforgiving sun with hands roughened by the handles of old shovels, earns a little over a cent. The caffeinated New Yorker will go about his day, vitalized by his drink, and make more money than that child farmer in Brazil will make in a year. At noon, this man might visit the same coffee shop and enjoy another cup, making that same child a cent richer than he was in the morning.

This sequence of events is repeated hundreds of millions of times, up to two billion times daily. Billions of dollars change hands because of coffee, but most people don’t know what their coffee truly costs, not in dollars, but in blood, past and present.

While the man in New York will treat this drink as a go-to morning drug, a necessity to brave the unquestionable weight of modern life, his equal, somewhere in a city nestled deep within the Iraqi desert dunes of the Al-Anbar province, considers it a drink that carries great honor and potential disgrace. Despite their differences, both men dip their hands into the globalized coffee market, sharing in its present, future, and ancient history. It begs the question then, of how men separated by culture, religion, location, and occupation came to drink the same drink but for vastly different reasons.

A Strange Drink In Muslim Lands

With coffee trading through Ottoman lands at full force, it was bound for a wide array of different coffee tastes to spring up according to the lands it spread to. When Levantine Arabs got their hands on the drink, and after it proliferated into every aspect of their lives, from coffee houses to wedding rituals, they started to change it. Initially, most coffee was drunk in the style people dub “Turkish Coffee,”, however, that changed in the Levant. Levantine coffee drinkers innovated greatly in coffee styles as their moderate environment allowed for the inclusion of diverse ingredients, some of which would have been unavailable in the rest of the Arab world.

Among the myriad of coffee inventions, made by the mixing and matching of hundreds of spices and herbs, three stand out due to their contemporary relevance. Lattes, as it seems, are not limited to Western coffee brands as we can find mentions of coffee with milk by the scholar and physician Ahmed Bin Omar Al Mazjed, who used it as medicine for stomach pains. Similarly, Ahmed Bin Ali Bin Bajahthab added sugar to his coffee to lessen its bitterness. Most bizarre and indicative of the moderate Levantine climate, Abdulrahman Bin Abi Bakr Al Sakran invented iced coffee by adding mountainous ice into his drink and consuming it after it cooled down.

In many ways, the introduction of coffee into Arab lands was proliferated and blocked by religious orthodoxy. Much like the bans that came into effect with introductions of many technologies and cultural innovations in our times, coffee was banned too. Scholars in many Islamic cities, like Cairo and Damascus, but particularly Mecca, moved the local governors to ban coffee, calling it heretical. To many, this is a familiar scene, as it continues to this day albeit with different products. Television, radio, movies, and even Pokemon cards, regardless of their usefulness as technology or recreation, were at some point banned for fear of sacrilege.

Those who lived through these bans would not have been surprised by the fact that coffee bans did the exact opposite of their purpose.

As more and more cities banned coffee, the demand surged. In a way, we can see a contemporary almost one-to-one parallel with American alcohol prohibition. Despite the clear difference, their Arabic linguistic similarities notwithstanding, coffee and beer drinkers in 15th century Arabia and Americans had lots in common. When mayors shut down liquor stores, pashas shut down coffee shops, and when coffee sacks were burned, alcohol was poured down the street. In both instances, the attempted ban of a profitable and sought-after product caused an underground market and demand to bloom, despite what authorities wanted.

Coffee and alcohol were legalized in their respective locations soon after the true consequences of their bans were found. Yet the legalization of coffee led to a major shift in world economies, and in some cases, histories, as coffee traders set their eyes on Europe.

Across The Mediterranean

Echoing ancient and contemporary trade lines, Europeans maintained a steady supply of coffee only via trade with North Africa, despite the reversed roles of today. Unlike the slim to no production of coffee, at least on a meaningful scale, the Middle East and North African markets of old traded many crops, resources, and products between continents. This ancient trade network facilitated the spread of coffee into Europe, beginning with Venice.

Despite early and continued success, the current state of MENA-European trade tells a very different tale from the networks that powered the spread of coffee across seas.

Though European farming of coffee was built upon imperialism in the global south, it got much bloodier as two catalysts, the slave trade and the Industrial Revolution took off. Millions died in different coffee plantations worldwide to fuel the European Industrial Revolution. These bloody consequences of a simple bean foreshadowed the much larger industry that was just about to bloom.

Out With the Old, In With The New

However, as the Industrial Revolution necessitated the creation of mass-produced products, like textiles and pottery, some began to give the once luxurious coffee product the same treatment.

By 1850, a young industrialist named William H. Bovee had noticed that workers in his native San Francisco faced a coffee issue. They had to roast, boil, and grind the beans, or visit a coffee shop and pay someone to do it for them. As a solution to this problem, Bovee started Folger’s, the world’s first instant coffee product. His product’s ease of production meant that coffee was brought outside its once decadent halls and into everyone’s home. This mass production of coffee required equal mass cultivation of coffee, which was met by the exploitation of slaves in countries conquered by European countries, or American enterprises. To Bovee, his capital venture helped his people, but to the millions it hurt, it was a scourge.

Folgers marked the beginning of a new age in which coffee was no longer a prized drink with a culture around it, but a commodity to be used pragmatically. Long gone were the “penny universities” where a penny’s worth of coffee would buy a man entry into a heated discussion of Averroes’s commentaries on Aristotle. In its place came the prized dollar, taking precedence over the drinker and the farmer.

As more people were enslaved and mistreated, coffee production continuously got cheaper, and more Europeans and Americans had coffee readily available. Bovee’s company was then used as a blueprint for many more companies in his day, and unfortunately, well into ours.

21st Century Drink

Examining the Bean Belt, a swath of land where coffee plantations thrive, one can notice that it houses the majority of the world’s largest coffee-producing countries in the third world, whereas the biggest coffee brands in the world are not. The reality of coffee production in the 21st century is that it is merely a continuation of 19th and 20th-century coffee slavery, only made legal through multiple loopholes.

Research by independent freedom and investigative journalism groups has revealed that many, if not all, coffee farmers worldwide suffer from a litany of injustices. Coffee farmers from the global south face improper working conditions, regular safety violations, wage reduction, and even unpaid child labor.

At the beginning of this article, a figure was given, and it is an accurate one. According to several different sources that investigated the unfair trade practices of the coffee industry, it has been revealed that most coffee farmers only see 7-10% profit on their coffee, while Brazilian farmers, particularly children, receive less than 2%. This exploitation of human capital, coupled with mass production effectively stamped out the traditional coffee markets in the Middle East as they were simply not profitable enough.

Yet, hundreds of years after Europeans wrestled the coffee trade out of Arab hands with mass production and price cutting, there seems to be a resurgence of interest in the Middle East. This resurgence promises to not only bring the drink back to its homelands but also improve worker conditions worldwide.

Back To Arabia

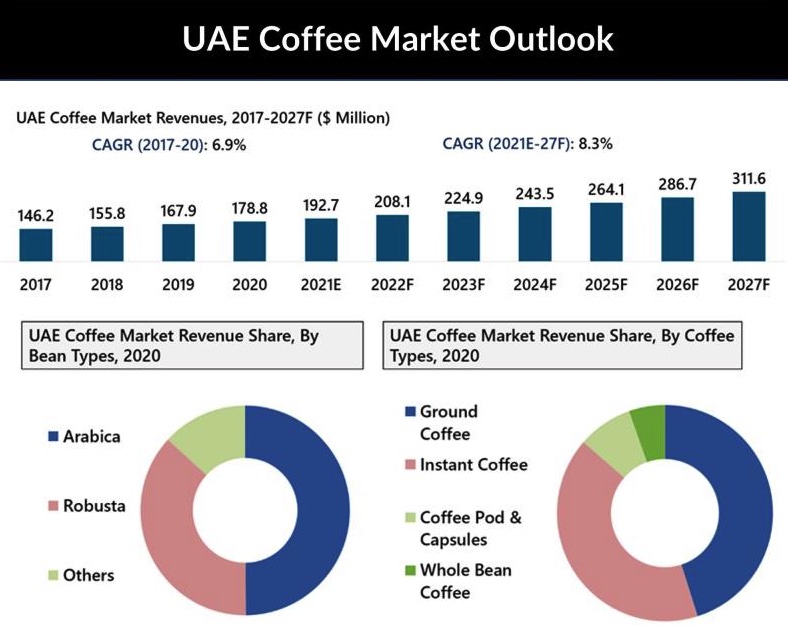

Much like an estranged son returns home, after braving the dangers of an unkind world, the coffee bean has come back to Arabia, its homeland. In fact, according to a 2022 Arabian Gulf Business Insight report, “The Middle East and North Africa’s (Mena) branded coffee shops market has grown 10.5 percent to 8,874 outlets in the past year,” with this report only two years old, it is almost a certainty that the upward trend has kept its pace.

Arab countries like Iraq, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, already with deep cultural ties to coffee, have invested heavily in their local coffee scenes in recent years. Across the Middle East, local brands of specialty coffee spring up almost every other day, each with its dedicated customer base and unique qualities. Where bedouin and tribal coffee rituals once reigned supreme, suburban communities have caught up. For many Arabs, an evening out entails, if nothing else, a sip of specialty coffee at one of many coffee houses in their city, or neighborhood at times. For those whose ancestors pioneered the coffee cup, the current state of the coffee market is unacceptable. Cultivation and roasting as areas of Western domination tiptoed around the edge of blasphemy to these inheritors, so, they sought to challenge them.

Despite most Arab countries, especially in the gulf, containing large swaths of desert, many coffee farming projects are underway. Oman and Saudi Arabia, already endowed with scarce arable land, are pioneering the 21st-century Arab coffee farming scene. The UAE on the other hand, has very little farmland that could be used for a nonessential crop like coffee. So, projects in the UAE are more or less restricted to vertical and small scafe artificial farms; the majority of these farms resembling Fujairah-based resident-started farms or corporate attempts like Elite Agro Projects in Abu Dhabi.

One such challenger is the Emirati-born Seed Coffee Roasters.

Upon entering their Abu Dhabi roastery, the scent of tens of different coffee blends immediately overwhelms your senses. Each whiff of air transports the visitor to a farm in the hills of Peru, Argentina, or Ethiopia. Their coffee is emblematic of the contemporary Arab coffee scene, highly detailed with different flavor undertones, scents, and even the elevation at which the beans were grown. But something else sets this roastery apart from its competitors, all of its beans are ethically sourced. This means that a farmer somewhere in Panama was paid their due wages, their children did not go hungry or need to sacrifice their education to work for cents to farm coffee alongside their ailing elderly parents.

Dinesh Balami, an employee at the roastery, revealed that they roast only a few several tons a month. He added that they “provide roasted coffee beans for about 70 cafes all over the UAE.”

At first, the figure appears dwarfed by multinational conglomerates that could easily surpass that in a day or two; speaking with their managing director, Samer Mashal, revealed why they chose the far more expensive and seemingly tedious route.

It is important to understand that the aim of roasteries such as this is not to overwhelm the market with better coffee beans. If that were the case, they would not have burdened themselves with caring about individual farmers. Nor would they have prepared different coffee brewing courses for people to take in order. Roasteries like Seed Coffee Roastery are symbolic of a reclamation trend.

The people of the “Global South,” young and old, those who saw the worst of exploitation and those who only heard of it, are reclaiming what was once theirs. Indeed, coffee itself, though a treasured commodity with great monetary value, is itself a symbol of an international struggle for those who were wronged. The story of coffee is one of discovery, fascination, veneration, desecration, and eventual redemption. Its resurgence in the Middle East is not merely a revolution of a lost market, but a warcry against the exploitative forces that took so much away from so many peoples.

It is a story of how discoveries carry a thousand potential outcomes. A single bean had the potential to cause riots, incur a cultural and educational revolution, enslave millions, power billions, and revitalize a colonized world. To some, a sip from a cup of coffee means nothing more than what it is, a sip of a bitter drink to wake up. But for those with refined palettes and a will to change the status quo, it is a reminder of what was and a prophecy of what could be if one dares.