By Salma Ghalwash

In the humid warmth of traffic-jammed downtown Dubai, fluorescent lights leak into the sky, heels clatter along the promenade, up and down crowded sidewalks and red carpets. Viewed through the looking glass, the city’s ever-churning tourism industry and advanced economic outlook put margins over culture. Dubai’s international regard has long stemmed from its standing as a preeminent commercial hub in the Middle East. But beyond metal-clad skyscrapers and the forgetfulness of modernity, the emirate’s artistic landscape has flourished from its roots in Bedouin oral tradition.

Garnering support from institutions such as Dubai Culture, government initiatives continue to develop and diversify the arts. Though there has been a surge in the creation of museums, galleries and indie cinemas over the past decade, theatre has remained an understated sector of Dubai’s creative industry.

As the nucleus of downtown, the Dubai Opera has become a site of awareness for the local theatre community and global performing arts. Its opening in August 2016 proved to be a success – the star tenor Placido Domingo’s performance of Verdi operas and Giordano’s Nemico della Patria sold out in 30 minutes.

Attracting over 200,000 visitors per year, the Dubai Opera “does not limit itself to opera, ballet and classical music performances,” says Programming and Events Executive Ayman Mahmoud. Instead, it is a “House of Cultures,” providing a diverse platform for world-class events.

Under its new head Paolo Petrocelli, the opera house is collaborating with prestigious theatres and opera houses, like the Teatro all Scala and Hungarian State Opera House.

In the future, the Dubai Opera aims to expand its creative in-house program and create an educational program for new professionals in the events industry.

“Building cultural bridges is at the core of what we do,” he adds.

From concerts featuring a hologram of the late Egyptian icon Umm Kulthum to traditional Tuareg melodies of the Grammy-winning rock band Tinariwen, a versatile repertoire is routine. Now, with over 40 events this season, the program continues to reflect the city’s multicultural identity.

But the opera house was an enduring project that did not always speak with resonant clarity.

Original designs for an opera house were initially part of an international competition that Zaha Hadid won. In collaboration with Patrick Schumaker, she proposed a striking structure resembling whirling sand dunes on an artificial island in Dubai Creek – a vision on par with New York’s Broadway or London’s West End. These proposals ultimately collapsed during the 2009 financial crisis.

Years later, a stable economy accelerated the development of the construction market. In a similar spirit, Emaar Properties, one of the world’s largest real estate companies, revived plans to build a new cultural district in March 2012. Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the Vice President, Prime Minister, and Ruler of Dubai, first announced its construction as an apt response to the need for more cultural establishments in the country.

“The cultural accomplishments of a nation define its character and individuality,” His Highness said.

Seafaring as a Muse

Danish architect Janus Rostock, leading a team at the company Atkins, designed the $330 million performance venue to compete with and complement the surrounding space – date palms, lancet buildings, and dancing fountains. As the first multifunctional complex in the region, an unorthodox shift from historic opera houses, the Dubai Opera occupies a remarkable performance space with ocean motifs and symbols of the UAE’s maritime history.

Enveloped in arabesque patterns of glass and metal, the exterior with its sloped roof is an ode to Emirati sailing vessels.

“The Bani-Yas tribe arrived in Dubai and settled on the shores of the creek,” Rostock says, explaining that the dhow was deeply “rooted in the Emirati Culture.”

Dhows are emblematic of livelihood as well as art in both crafting and the sorrowful songs of the fishermen at sea. Astrolabes are etched into the floors, which mariners used for prayer and navigating open waters. With dozens of lamps that look like jumping sea creatures and furniture laminated with lustrous mother of pearl from India, the opera recalls a legacy of prosperity through pearl diving, fishery and trade.

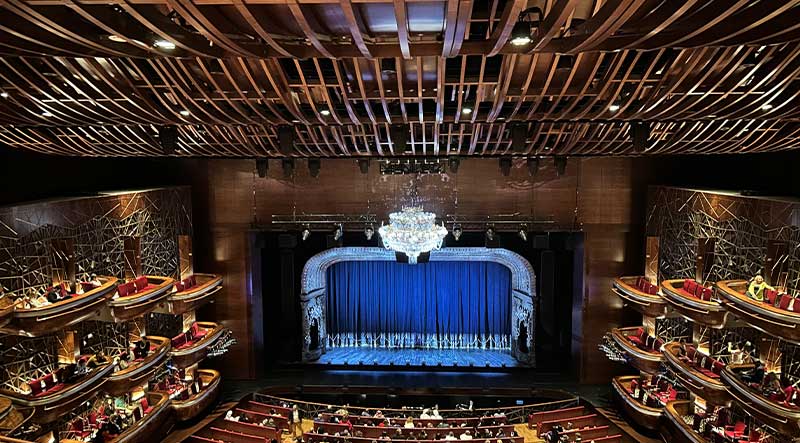

Descending dramatically from the ceiling at the center of the opera is the “Symphony,” a chandelier that glows in the rhythm of a beating heart. Handcrafted by the Czech company Lasvit, the 11-meter-long light sculpture gives the impression of water with 30,000 pearls and 3,000 internal LED sources. The centerpiece’s light can be programmed to match music.

“I aimed for a very organic appearance,” says Libor Sostak, a designer at Lasvit. “Visitors will naturally be drawn to light and music, forming a beating heart within the space.”

The waiting area, also called the Majlis, is adorned with art. Pictures of swirling dancers hang on the walls. Japanese photographer Shinichi Maruyama combined 10,000 images of choreographed dancers to create each photo, capturing the fluidity of motion and the idea of impermanence. Separating the Majlis from the atrium, a large-scale wall installation protects the privacy of the seating space. Contemporary Korean artist Ran Hwang individually placed 160,258 crystals, beads and pins on Plexiglas in the shape of a chandelier covered in cobwebs.

The stage wasn’t fixed: the auditorium, which houses musicals, opera, ballets, concerts, stand-up comedy, exhibitions, weddings, iftar or virtually any event, is easily transformed. The ceiling looks like the hull of a wooden ship, providing artistic and functional value. To modify the space, the boat-shaped side balconies are removable and the floor is made up of 32 wagon panels that fit together like puzzle pieces. There are three novel configurations. One is a concert hall where reflectors are lowered onto the stage and the proscenium has disappeared. It can also be rearranged either into a traditional proscenium arch theatre or a flat floor space with no stall which is extended backstage. The auditorium’s technology, lighting and acoustics had to be adapted to multiple modes.

During the afternoon, the grand theatre felt empty. Amid tangled lines, jerking wires and ropes, the crew were weaving together the production with unceasing energy.

Three men, dressed in black from head to toe, in deep discussion, had gathered on one side of the backstage area that was nearly enclosed in red barriers. Hunched over a bank of computers nearby, another man’s lanyard clacked against the table. His eyes, behind the glint of his glasses, darted between 3D models of elaborate sets on one screen and blinking colors on the other.

Dusty gold rococo-style chairs and folding screens were placed in an organized clutter, almost merging with other scenes.

Michael Duncan, the technical manager for “The Phantom of the Opera,” maneuvered through boxes and towering structures.

The Opera Ghost

Based on the novel by French journalist and writer Gaston Leroux, Andrew Lloyd Webber’s “The Phantom of the Opera” graced the stage from Feb. 22 to March 10. At the Opéra Garnier in Paris circa 1880, soprano Christine Daaé believes she is being taught by an angel sent by her dead father. Instead, her teacher is a disfigured composer, the Phantom, who wreaks havoc in his deadly obsession for her. The mega-musical, known for its unashamedly maudlin, dramatic spectacle, became the longest-running show on Broadway. It also is the longest-running show at Dubai Opera.

“Our touring company has 80 people on the move,” Duncan says, including actors, musicians, crew, carpenters, management and one prosthetics artist. But the production has over 20 people working as local crew to assist as sound engineers, stagehands, loaders, makeup artists and wardrobe staff. They also recruited specialists to rig the chandelier from electric hoists and winches secured to the roof.

It was a long arduous process, taking four and a half days of work before opening night. Time was a luxury. And yet, cumulatively, the tasks required too much precision to be ladened with reckless rushing. Speakers, lighting, sound consoles and props are tailor-made for the play and freighted to the venue.

“Everything,” he says, “Everything technical is brought in just for this show. It’s very, very specific.”

The humming industrial noise was interrupted, sometimes, by a clang from the wall, a ladder, or a box. Quiet, persistent.

The loading dock was naturally too small, so the team had to reconstruct the settings of each scene. Whether it was the candelabra-filled subterranean lair or an embellished ballroom comprised of antique mirrors, the crew seamlessly switched between set designs. They ensure the dynamic mechanisms of the rotating cylindrical wall and the ghost’s gondola as it glides through a low-hanging fog.

Until an hour before the show, crew members reset the components to their proper positions, conduct general maintenance and test various elements here and there. Afterward, the cast does a soundcheck and the orchestra tunes their instruments.

Thick, heavy blue drapes conceal the stage. The lights dim, casting long shadows on the proscenium portal. An auctioneer bids off memorabilia – a strange musical box and a suspended chandelier. The light flickers dauntingly, sweeping the Paris Opera House into the past. As the air erupts with excitement, the curtains lift, revealing a diegetic rehearsal of the classic opera Hannibal. A full corps de ballet pirouettes across the stage, their red and green garments flowing like a stream.

Lloyd Webber’s score is a pastiche of 1980s heavy metal and pop with fragments of gothic allure. It’s difficult to discern what is the most striking aspect of the “Phantom.” Is it the chandelier that hovers over the audience like the sword of Damocles, the Gilded Age glamor of costumes, the intensity of the displays or the vocal pyrotechnics of the ensemble?

The Phantom was more of an enthusiast than an exceptional composer. He forms an impregnable bond with Christine over music, imploring her to sing. Just as she succumbs to the “power of the music of the night,” so too does the audience find themselves beguiled by the timeless score. During the intermission between acts, attendees would hum the play’s thundering organ chords. Experiencing music with little visual engagement or light enhances its impact on the listener. In doing so, they appreciate the primeval potential of the human voice and what can be sensed in the present. A shared experience of immersive theatre that can only exist between a performer and viewer.

As the cast takes their bow and is met with a roar of applause, they feel they “are helping create a new theatre scene in the region,” Nadim Naaman, who plays the Phantom, said. After a few minutes, he raised his hands to calm the ovation.

If the performance wasn’t enchanting enough, he greeted the audience in Arabic, much to their delight, “Sayidati wa sadati [Ladies and gentlemen].”

The Lebanese-British actor spoke of his parents. How they had met in Dubai but relocated to London two years before his birth. He has visited the city for three decades, so it occupies “a special place in his heart.”

Before a capacity crowd, he urged, “support the arts, support theatre and I promise you a hundred more shows like this to come.”

“The Phantom of the Opera” always drew large audiences, nurturing lasting affection and encomia for histrionics from fans for 37 years. For Miriam Bashee, the Phantom was the most enamoring musical she had ever seen. From a young age, her multiple instances of operagoing were in some sense a spellbinding rite of passage or glitzy gateway to theatre. This viewing differed from the four times she saw it in London, too. Though this was the first time she watched the “Phantom,” Prathana Chaturvedi attended Swan Lake at the Dubai Opera last year.

“It’s a worthwhile show and everyone should come see it,” says Isabella Martin, noting that she watched it the year before as well.

The touring company has packed its wigs, tech and revolving staircases, and another production fills the space left behind. Prosperous and globalized, yet nostalgic and eclectic, Dubai Opera lies at the intersection of artistic integrity and commercial success. The opera house is far beyond introducing a venerable art form to a nation with little native operatic tradition.

The survival of theatre isn’t a question but a refuge for many. Maybe the answer is just a little more opera.