By Inas Faiza Naravar Mohideen

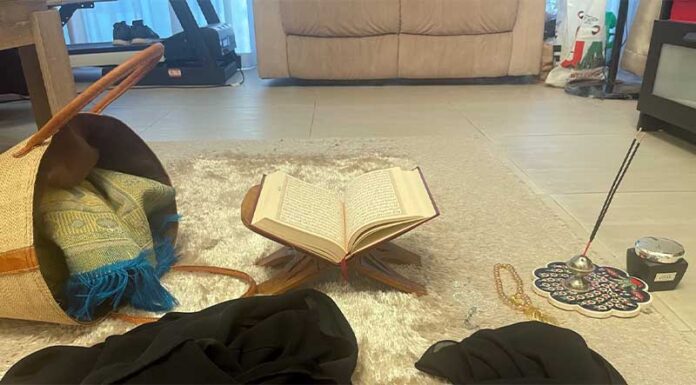

The first sign was always the scent of sandalwood from the hall. At 5:25 p.m., Shafana’s mother would light the incense sticks. By 5:30 p.m., the elevator would ding, followed by heavy footsteps echoing down the corridor, each one announcing his arrival. That was usthad.

He was a tall, lean Bangladeshi man with a long white beard flowing like wisps of cloud and a taqiyah perched on his head like a crown of devotion. He always wore a spotless white kandura, sometimes in a pale golden shade, ironed so perfectly it looked brand new every single time. There was a peculiar fragrance of attar that clung to him, overpowering the scent of the incense sticks. Even on the windiest days, his kandura remained pristine, reflecting the discipline and care he carried in his profession.

He would sit cross-legged on the floor, never on a chair, with the Holy Quran resting between them. Shafana would sit opposite to him, half-asleep from her afternoon nap, never making eye contact. When he recited, his body swayed slowly forward and back, a rhythm she soon found herself unconsciously adopting. His index finger traced the lines on the page with perfect precision.

“He knew exactly which line on the page I was reciting. If I skipped a line, he would stop me immediately and make me recite it again,” Shafana said with a cheeky grin tugging at her lips.

She would race through the recitation, flipping the pages quickly just to finish. After fifteen minutes, she would close the Holy Quran. Usthad would look at her in awe and ask, “Bas?” [That’s it?] She would tilt her head and smile, her silent plea to be done. Sometimes, he would let her close the Quran early; other times he would insist she read one more page.

Usthad had four children and was their sole provider, pedaling his old bicycle from house to house to teach the Holy Quran. The work did not pay him much, yet he never showed any trace of complaint. He always carried a warm smile, especially when he recited in that calm and melodic voice.

Shafana never spoke Urdu, but she could understand enough, and usthad spoke in broken Urdu and English. Despite the difficulty, he never let it stop him from talking to her.

“Namaz kiya?” he would ask.

[Have you prayed?]

She would nod.

“Sach?” [Really?]

“Yes,” she would affirm.

“Pray five times a day… miss salah… Allah no like. My house…my child miss prayer, he no get food…,” he would say, laughing.

“Khana kaya aaj?” [Have you eaten today?]

She would nod again with a smile.

“Kya khaya?” [What did you eat?]

“Rice,” she would always say, as she did not know how to translate other dishes.

Sometimes he would ask playful, random questions about cricket matches. Other times, he would smile and say, “I talk you … you look like my Fatima. Same same smile. I no talk others like this…”

One evening, he finished a lesson and carefully placed the Quran back on the shelf. From his pocket, he pulled a worn, creased photograph. “My Fatima,” he said, his thumb stroking the faded image. “She doing marriage.” The pride in his voice was edged with a new, sharp worry.

In the weeks that followed, Shafana noticed some changes in him: the new lines of fatigue around his eyes and the way his gaze grew distant during their lessons. He began asking Shafana’s mother, “You know other family need teacher?”

For the first time, she felt moved to do something for him. The following week she made a small congratulatory card for Fatima and found herself eagerly awaiting the sound of his footsteps, hoping her small gift would light up his eyes.

The clock hit 5:30 p.m., but the elevator stayed silent, and his footsteps never came.

“Mama, where’s usthad ?” she asked, a knot of worry forming in her stomach.

Her mother replied, “Ah, he came this morning when you were at school to get his final payment.” She opened the freezer to show a big tub of chocolate ice cream. “He bought this for you. He is moving back to Bangladesh due to some financial issues.”

“I wish I had at least said goodbye,” she whispered, looking away, her face flushed with remorse. The kindness of his gift, given amidst his own struggles, tightened her throat. Her card, still in the drawer, was now a monument to everything left unsaid.

“Ah, we never knew his name. We only called him usthad,” she said, a faint smile crossing her lips to mask her sadness. Beneath it, lingered a quiet guilt for never being able to help him.

Now, years later, she has no picture, no number, no proof of his existence. The only way to feel his presence is to recreate the sacred space they shared together: to light the incense sticks and read the Holy Quran.